JEFFREY HARRISON

An interview by Elisabetta Beneforti

1. Inside your poems a lyric soul coexists with a narrative one, so different impulses are interwoven in verses ….do they go parallel or do they feed each other?

You’re right that they are different impulses—the urge to express an emotion in beautiful language vs. the need to say what happened—but they aren’t mutually exclusive. I actually see them as part of a spectrum or continuum, with extreme lyric at one and perhaps straight chronological narrative at the other end. You can write a poem from anywhere on that spectrum. Mine tend to be somewhere in the middle, but some poems will be closer to the lyric end while others will move closer to the narrative end. My old teacher Stanley Plumly writes about this in his essay “Narrative Values, Lyric Imperatives” (in his prose book Argument and Song)—both how narrative (though probably not straight narrative) is necessary to the lyric (to keep the poem moving), as well as the idea that most poems have a narrative source but can be written from somewhere close to that source or from further away from the source (i.e., more lyrically). The poet Ellen Bryant Voigt also has some interesting things to say about narrative and lyric in her book The Flexible Lyric. She tends to highlight the differences between lyric and narrative—especially the idea that they have entirely different structures—but also points out that, in lyric, the narrative becomes “back story,” conveyed indirectly through the voice of the poem’s speaker (who in a sense is a character in the story). That idea seems to fit with Plumly’s notion of the narrative source and also with my sense of the lyric/narrative spectrum. It is probably voice, or tone, that seamlessly holds the lyric and narrative modes together—because the voice both tells the story and conveys the emotion.

2. No doubt there are so many links connecting your five poetry collections and that’s why we can talk about them being ‘memor-like’…. Can we consider them as real parts of just a “canzoniere”?

You are not the first person to make this observation about the connection between my books. What may surprise you is that, unlike some poets (I believe Louise Glück is an example) I don’t even think of my individual books as a whole while I’m writing the poems—or at least not until later in the process. For better or worse, I write the poems I am moved to write as they come to me, one at a time… though sometimes one will lead to another. Then, when I have enough poems, I’ll look for an organic way to arrange the book as a whole, some kind of arc or set of organizing principles. I am never thinking about how one book relates to another. Even so, I can understand how, when a reader steps back and considers all the books together, they may seem to follow one from the other, like sections of a poetic memoir. This effect, I think, has to do with the kind of poems I tend to write—which, for the most part, are poems that come out of an actual life. So the books feel—and, in some sense, are—accounts of my life during the period when they were written. For example, Incomplete Knowledge, my fourth book, contains a lot of poems about my brother’s suicide, and there are a few more of those in my most recent book, Into Daylight. In fact, there is one poem in Into Daylight (the sestina “Essay on a Recurring Theme”) that actually comments on the poems in Incomplete Knowledge—that is an exception for me. In a broader sense, Into Daylight is not a book about my brother’s suicide but a book about the decade after—the next chapter, so to speak. But within that chapter there are a lot of different kinds of poems: love poems, poems inspired by other writers, poems about the natural world, etc. What connects them all, again, may be a sensibility, a voice.

3. Now let’s talk about your latest collection Into Daylight (Tupelo press, 2014) which introduces itself through a very evocative cover….how was this book born and what do its poetic materials consist of?

After I wrote all the poems about my brother’s suicide that appear in the second half of Incomplete Knowledge, I had no idea where to go next. What could I write after writing those poems of intense grief? I answered that question very slowly, poem by poem. It turned out that I had a little more to say about my brother, but also about a lot of other things. Most of the poems in Into Daylight (especially after the first section) have nothing to do with my brother’s death, though his absence may hover behind some of the poems that are not explicitly about him. If the book is about anything, it’s about reconnecting with the world, with perception, and with poetry during the decade after my brother’s death—of finding again my proper relationship with the world, of rediscovering delight even while giving voice to pain and sadness.

You mentioned the cover, so I thought I would say something about the way the book’s title and the cover play off each other. The title suggests a movement out of darkness and into the light. The cover image, with its gloomy beauty, captures that movement in the early or middle stages—no longer in darkness, but not yet in the full light, either—whereas the title emphasizes a later stage of the process, of actually coming into the light. I had imagined a brighter cover image, perhaps a blue sky full of big clouds, like something out of Van Ruisdael, so I was at first resistant to that foggy snow scene. But I came to feel that the discrepancy between the title and the cover created an interesting tension.

4.The American poets: who do you consider a master of yours or a travel-mate?

One of my favorite poets—a real touchstone for me—has always been Elizabeth Bishop. I read her in my early twenties and felt instantly that her distinctive, natural voice was speaking directly to me. Now of course she is famous and there is a whole critical industry around her work, but at that point she was like a well-kept secret—it was her friend Robert Lowell who was famous. After her, there are too many to name, and I know I would probably forget some, so maybe I’ll leave it there. But I will say that Into Daylight contains a number of references and homages to other writers (including Robert Frost, Whitman, Richard Wilbur, and Mark Strand), but many of them aren’t American (John Clare, Hopkins, Han Shan, Catullus, Edward Thomas, Tolstoy, Virginia Woolf, etc.).

5.…and referring the Italian scene, which poets can’t you give up reading? Recently you spent some weeks in Liguria, a beautiful Italian landscape….

I’m ashamed to say that my familiarity with Italian poetry is not what it should be, though I did start early, in college. I went to Columbia, where Dante’s Inferno was a permanent part of the syllabus. (Later, I read the rest of the Divine Comedy.) I also took a class called “The Italian Sonnet,” which included the Vita Nuova, Petrarch, Michelangelo, and many others. The modern Italian poet I’ve returned to most is Montale, and I took him with me to Bogliasco, so I could reread him “on location.” There were details from his poems all around me, starting with lemon trees in the garden below my room (as in his poem “I Limone”) and including a wall topped with broken glass along the lane I had to walk down to get into town (like the one in his poem “The Wall”). I ended up writing a little poem about that experience, beginning with those shards of glass and ending with the tiny beads of smooth glass I found hidden among the rocks on the beach. I also took a huge anthology of twentieth-century Italian poetry with me, and I reread poets I’d read before, like Ungaretti and Pavese, as well as ones I’d never read, like Giorgio Caproni, Pasolini, and Umberto Saba.

6.What do you think about the role of the poetry inside the contemporary environment?

It’s complicated. More people are reading and writing poetry than ever before, but in terms of society as a whole, it has never been more ignored. It doesn’t help that the dominant mode in America right now tends toward ironic obfuscation—as if the poets had abdicated any attempt to communicate and lived in fear of encountering an actual emotion. This only further marginalizes poetry. On the other hand, poetry can’t compete against mass media and probably shouldn’t try. It will be kept alive by those who are still engaged in the perhaps old-fashioned (or is it timeless?) struggle to say the unsayable and create beauty in the process.

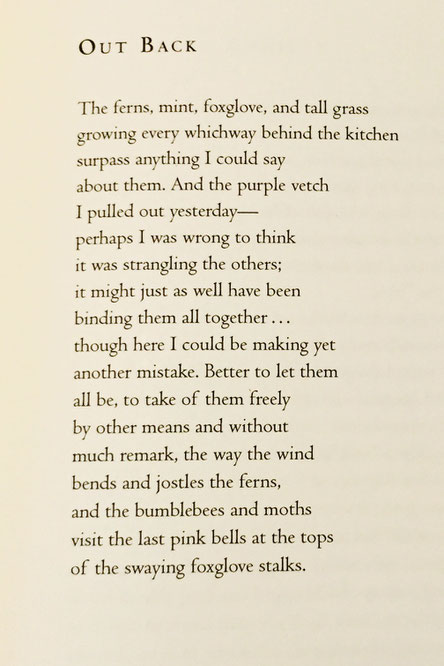

Poems

LISTENING TO VIRGINIA

(Virginia Leishman reading To the Lighthouse)

Driving around town doing errands,

I almost have to pull to the side of the road

because I can’t go on another minute without

seeing the words of some gorgeous passage

in the paperback I keep on the passenger seat…

but I resist that impulse and keep listening,

until it is almost Woolf herself sitting beside me

like some dear great aunt who happens to be a genius

telling me stories in a voice like sparkling waves

and following eddies of thought into the minds

of other people sitting around a dinner table

or strolling under the trees, pulling me along

in the current of her words like a twig riding a stream

around boulders and down foaming cascades,

getting drawn into a whirlpool of consciousness

and sucked under swirling into the thoughts of

someone else, swimming for a time among the reeds

and glinting minnows before breaking free

and popping back up to the surface only to discover

that in my engrossment I’ve overshot

the grocery store and have to turn around,

and even after I’m settled in the parking lot

I can’t stop but sit there with the car idling

because now she is going over it all again

though differently this time, with new details

or from inside the mind of someone else,

as if each person were a hive, with its own

murmurs and stirrings, that we visit like bees,

haunting its dark compartments, but reaching

only so far, never to the very heart, the queen’s

chamber where the deepest secrets are stored

(and only there to truly know another person),

though the vibrations and the dance of the worker bees

tell us something, give us something we can take

with us as we fly back out into honeyed daylight.

From Into Daylight (Tupelo Press, 2014).

FOR CLARE

I saw a brown shape in the unmown grass,

half-hidden in a tuft, and crouching down

to get a closer look, I found a young rabbit,

no bigger than my hand, trembling there

in its makeshift nest. And I thought of John Clare:

this was one of his creatures in my own yard,

pressed close to the earth, timid and alone,

almost a visitation from the “bard

of the fallow field and the green meadow,”

who loved the things of nature for what they are.

It didn’t run away when I parted the grass

and stroked its soft fur, but quivered in fear,

the arteries in its small translucent ears

glowing red, its dark eyes wide. I thought

of keeping it, at least for a few days,

feeding it bread and lettuce, giving it water

from an eye dropper. Then it did run away

in little bounds to the edge of the woods,

and into the woods. I thought again of Clare,

how, after he escaped from the asylum,

he walked almost a hundred miles home,

lost, delusional, beyond anyone’s care,

waking soaked in a ditch beside the road,

so hungry that he fed himself on grass.

From Into Daylight (Tupelo Press, 2014).

VISION

I just got back from the eye doctor, who told me

I need bifocals. She put those drops in my eyes

that dilate the pupils, so everything has

that vaseline-on-the-lens glow around it,

and the page I’m writing on is blurred

and blinding, even with these sunglasses.

I’m waiting for the “reversing drops” to kick in

(sounds like something from Alice in Wonderland),

but meanwhile I like the way our golden retriever

looks more golden than ever, the way the black-eyed

Susans seem to break out of their contours, dilating

into some semi-visionary version of themselves,

and even the mail truck emanates a white light

as if it might be delivering news so good

I can’t even imagine it. Of course it’s just bills,

catalogues, and an issue of Time magazine

full of pictures of a flooded New Orleans

that I have to hold at arm’s length to make out:

a twisted old woman sprouting plastic tubes

lies with others on an airport conveyor belt

like unclaimed luggage, and there’s a woman feeding

her dog on an overpass as a body floats below.

Maybe we need some kind of bifocals

to take it all in—the darkness and the light,

our own lives and the lives of others, suffering

and joy, if it is out there—or something more

like the compound eyes of these crimson dragonflies

patrolling the yard, each lens focused on some

different facet of reality, and linked to a separate

part of the brain. We would probably go crazy.

In my own eyes with their single, flawed lenses,

the drops have almost worn off now, and my pupils

are narrowing down, adjusting themselves

to their diminished vision of the world.

From Into Daylight (Tupelo Press, 2014).

CROSS-FERTILIZATION

It’s come to this: I’m helping flowers have sex,

crouching down on one knee to insert

a Q-tip into one freckled foxglove bell

after another, without any clue

as to what I’m doing—which, come to think of it,

is always true the first time with sex.

And soon Randy Newman’s early song

“Maybe I’m Doing it Wrong” is running

through my head as I fumble and probe,

golden pollen tumbling off the swab.

I transported these foxgloves from upstate New York,

where they grow wild, to our back yard

in Massachusetts, and I want them to multiply,

but the bumblebees, their main pollinators,

haven’t found them, and I’m not waiting around.

The only diagram I found online portrayed

a flower in cross section, the stamens extending

the loaded anthers toward the flared opening,

but the text explained, “The female sexual

organs are hidden.” Of course they are.

Which leaves me in the dark, transported back

to a state of awkward if ardent

unenlightenment, a complete beginner

figuring it out as I go along,

giggling a little and humming an old song

as I stick the Q-tip into another flower

as if to light the pilot of a gas stove

with a kitchen match, leaning in to listen for

the small quick gasp that comes

when the flame makes contact with the source.

From Into Daylight (Tupelo Press, 2014).

MEDUSA

(New England Aquarium)

Like fireworks, but alive,

a nebula exploding

over and over in a liquid sky,

this undulant soft bell

of jellyfish glowing orange

and trailing a baroque

mane of streamers, so

exquisite in its fluid

movements you can’t pull

your body away, this lucent

smooth sexual organ

ruffled underneath

like a swimming orchid,

offers you a second-

hand ecstasy, saying

you can only get

this close by being

separate, you can only

see this clearly

through a wall of glass,

only imagine

what it might be like

to succumb to something

beyond yourself,

becoming nothing

but that pulsing,

your whole being reduced

to the medusa,

tentacled tresses flowing

entangled in a slow-motion

whiplash of rapture—

while you stand there,

an onlooker

turning to stone.

From Feeding the Fire (Sarabande Books, 2001).

FORK

Because on the first day of class you said,

“In ten years most of you won’t be writing,”

barely hiding that you hoped it would be true;

because you told me over and over, in front of the class,

that I was “hopeless,” that I was wasting my time

but more importantly yours, that I just didn’t get it;

because you violently scratched out every other word,

scrawled “Awk” and “Eek” in the margins

as if you were some exotic bird,

then highlighted your own remarks in pink;

because you made us proofread the galleys

of your how-I-became-a-famous-writer memoir;

because you wanted disciples, and got them,

and hated me for not becoming one;

because you were beautiful and knew it, and used it,

making wide come-fuck-me eyes

at your readers from the jackets of your books;

because when, at the end of the semester,

you grudgingly had the class over for dinner

at your over-decorated pseudo-Colonial

full of photographs with you at the center,

you served us take-out pizza on plastic plates

but had us eat it with your good silver;

and because a perverse inspiration rippled through me,

I stole a fork, slipping it into the pocket of my jeans,

then hummed with inward glee the rest of the evening

to feel its sharp tines pressing against my thigh

as we sat around you in your dark paneled study

listening to you blather on about your latest prize.

The fork was my prize. I practically sprinted

back to my dorm room, where I examined it:

a ridiculously ornate pattern, with vegetal swirls

and the curvaceous initials of one of your ancestors,

its flamboyance perfectly suited to your

red-lipsticked and silk-scarved ostentation.

That summer, after graduation, I flew to Europe,

stuffing the fork into one of the outer pouches

of my backpack. On a Eurail pass I covered ground

as only the young can, sleeping in youth hostels,

train stations, even once in the Luxembourg Gardens.

I’m sure you remember the snapshots you received

anonymously, each featuring your fork

at some celebrated European location: your fork

held at arm’s length with the Eiffel Tower

listing in the background; your fork

in the meaty hand of a smiling Beefeater;

your fork balanced on Keats’s grave in Rome

or sprouting like an antenna from Brunelleschi’s dome;

your fork dwarfing the Matterhorn.

I mailed the photos one by one—if possible

with the authenticating postmark of the city

where I took them. It was my mission that summer.

That was half my life ago. But all these years

I’ve kept the fork, through dozens of moves

and changes—always in the same desk drawer

among my pens and pencils, its sharp points

spurring me on. It became a talisman

whose tarnished aura had as much to do

with me as you. You might even say your fork

made me a writer. Not you, your fork.

You are still the worst teacher I ever had.

You should have been fired but instead got tenure.

As for the fork, just yesterday my daughter

asked me why I keep a fork in my desk drawer,

and I realized I don’t need it any more.

It has served its purpose. Therefore

I am returning it to you with this letter.

From Incomplete Knowledge (Four Way Books, 2006).

THE NAMES OF THINGS

Just after breakfast and still

waking up, I take the path cut

through the meadow, my mind caught

in some rudimentary stage,

the stems of timothy bending

inward with the weight of a single

drop of condensed fog clinging

to each of their fuzzy heads

that brush wetly against my jeans.

Out on a rise, the lupines stand

like a choir singing their purples,

pinks and whites to the buttercups

spread thickly through the grasses—

and to the sparser daisies, orange

hawkweed, pink and white clover,

purple vetch, butter-and-eggs.

It’s a pleasure to name things

as long as one doesn’t get

hung up about it. A pleasure, too,

to pick up the dirt road and listen

to my sneakers soaked with dew

scrunching on the damp pinkish sand—

that must be feldspar, an element

of granite, I remember from

fifth grade. I don’t know what

this black salamander with yellow spots

is called—I want to say yellow-

spotted salamander, as if names

innocently sprang from things

themselves. Purple columbines

nod in a ditch, escapees

from someone’s garden. It isn’t

until I’m on my way back

that they remind me of the school

shootings in Colorado,

the association clinging to the spurs

of their delicate, complex blooms.

And I remember the hawk

in hawkweed, and that it’s also

called devil’s paintbrush, and how

lupines are named after wolves . . .

how like second thoughts the darker

world encroaches even on these

fields protected as a sanctuary,

something ulterior always

creeping in like seeds carried

in the excrement of these buoyant

goldfinches, whose yellow bodies

are as bright as joy itself,

but whose species name in Latin

means “sorrowful.”

From Incomplete Knowledge (Four Way Books, 2006).

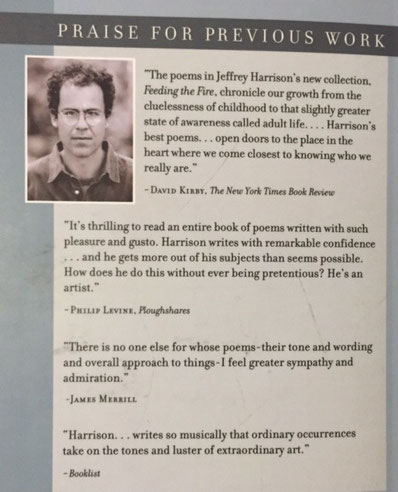

Jeffrey Harrison is the author of several collections of poetry, including Incomplete Knowledge (2006), a runner-up for the Poets’ Prize; Feeding the Fire (2001); and The

Singing Underneath (1988), chosen by James Merrill for the National Poetry Series.

Harrison’s honors include the Lavan Younger Poets Award from the Academy of American Poets, the Amy Lowell Traveling Poetry Scholarship, two Pushcart Prizes, and fellowships from the National

Endowment for the Arts and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

Harrison has taught at George Washington University, Phillips Academy, the University of Southern Maine, and Framingham State University. He lives in Massachusetts..